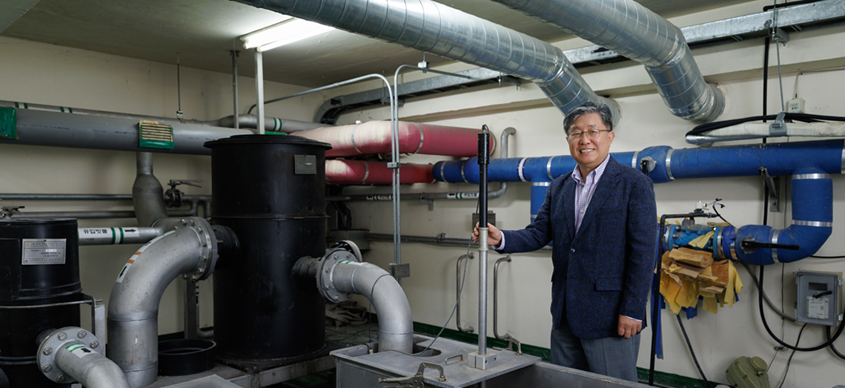

Did you know that there are rainwater storage tanks on the campus? Beneath Building 39, there is a rainwater tank more than four meters deep, capable of storing up to 250 tons of rainwater collected on campus. The idea for channeling rooftop rainwater into storage was first proposed by Professor Emeritus Han Moo-Young during the building's design phase. Professor Han of the Institute of Construction and Environmental Engineering, who graduated from the Department of Civil Engineering, gained practical experience working for construction companies and on-site projects in Middle Eastern countries. While working in Iraq, he witnessed people living without proper water and sewage systems and with a lack of drinking water, which inspired him to pursue further studies abroad.

“We made a replica of the Cheugugi, the rain gauge invented during King Sejong’s era, and placed it in our lab. To me, the Cheugugi is like a spiritual anchor.” (Professor Han)

“There were so many people living in poor sanitary conditions. My field is meant to serve public health and the environment, so I felt the need to use my expertise. Based on my field experience, I focused my research on water treatment and water quality.

In most cities, water and sewage systems are centralized, using dams and pipelines connected to purification plants. But for rural or remote areas, the cost of such infrastructure is a huge burden. Developing countries often lack technical experts and face maintenance challenges. I wanted to find solutions, because no one should be left behind when it comes to water. Moreover, the vulnerability of large-scale systems is becoming more apparent due to the climate crisis. That’s why I became interested in decentralized systems as an alternative.”

Professor Han has been designing and developing decentralized rainwater harvesting systems for use in individual schools and homes.

At Gwanak Campus, rainwater storage tanks are not only located beneath Building 39, but also in the dormitory area (with a 200-ton facility), at the main gate (60,000 tons), in Budeulgol (15,000 tons), and at the Engineering Waterfall (5,000 tons). These tanks collect rainwater by intercepting it as it flows through the gutters. An automatic filter removes dust and leaves before the rainwater enters the tanks. At Building 39, the stored rainwater is used for flushing toilets. The system operates without chemical additives or powered machinery, relying solely on natural processes.

There are about 8,000 toilets at Seoul National University. Professor Han converted 500 of them to use rainwater instead of regular tap water.

“During droughts, people anxiously wait for rain, but when it finally comes, much of the rainwater simply goes to waste. It felt like such a waste to just let it go. At first, I thought about using my knowledge of water treatment to reuse rainwater for flushing toilets. As I treated the rainwater, I found that its quality was good enough to drink. In the past, I used to think of rainwater as something to be discarded, or even as ‘acid rain’ that was harmful.

When rainwater is stored in the tank, impurities naturally settle to the bottom through sedimentation. To maintain water quality, we installed a ‘biofilm’ in the tank. Biofilm is a slimy layer—like the coating you find on rocks in a stream—that helps purify the water. The microorganisms in the biofilm naturally clean the water, making it an eco-friendly solution.”

Some families don’t have enough water, so we helped them become more self-sufficient by installing rainwater tanks.

Professor Han explained that as his perspective on rainwater changed, he began to think of people in countries suffering from water shortages. This led him to collaborate with the Cambodian Ministry of Education to install rainwater drinking facilities in schools that require no maintenance costs. These facilities are managed by students, known as “BiTS (Bi[Rain] Teacher Student)” youth leaders.

Professor Han has expanded his efforts beyond Cambodia’s “BiTS” program to establish “Rain Schools” in five countries along the Mekong River. These Rain Schools are equipped with rainwater drinking facilities. In November this year, 20 teams from Rain Schools will visit Korea. As part of a cultural exchange, a dance contest will be held, and the winning team will receive a rainwater harvesting facility, which will be installed at their school free of charge.

“Maintenance is always an issue for any kind of facility. Many projects tend to lose momentum after a year,” Professor Han explained. “That’s why we created science clubs at the schools and called them ‘BiTS.’ The students loved the name, as it sounds like ‘BTS,’ the famous music group. As part of BiTS, students measure both the quantity and quality of the rainwater and share the results with their families and friends. As they began using bottled rainwater that was safe to drink, the students’ expressions brightened and the atmosphere in the village changed. BiTS remains active and continues to thrive.”

The BiTS program also includes activities that encourage students to explore the wisdom of their Cambodian ancestors. Professor Han explained that he hoped students would feel proud as they reflected on their ancestors who built artificial lakes and canals at Angkor Wat. “Cambodians already have a rich tradition and knowledge of water management,” he noted.

Professor Han also worked on flood prevention and started a rooftop garden on top of Building 35. Local residents, students, international students, and professors all pitched in to take care of the garden together. Some local residents would come early in the morning to pull weeds and plant things like lettuce, perilla leaves, potatoes, and corn. When it was time to harvest, they made bibimbap with the vegetables and shared it with the students. International students used the cabbage they grew to make kimchi, and during Chuseok, they even made songpyeon (rice cakes) together. A lot of international students said that even after going back to their home countries, they often thought about the rooftop garden and missed those memories.

The rooftop garden was always lively thanks to the local residents who took part. Professor Han wanted to turn the rooftop into a WEFC space—a place for Water, Energy, Food, and Community.

“When rainwater from a building all rushes down at once, that’s when you get floods. I wanted to prove that if each building just managed its own rainwater, it could make a difference—so I even used my own money to build a rooftop garden. Here’s how it works: if there’s a heavy rain, say 100mm, the rainwater collects on the roof, creating a 10cm layer. We made a 10cm-deep space for water under the rooftop garden, then covered it with about 15cm of soil. This way, even if 100mm of rain falls, none of the water overflows off the building. That’s how you prevent flooding. The water stored under the garden slowly evaporates, and as it does, it absorbs heat from the building—which actually helps cool it down, too.”

The rainwater tank under Building 39 has been running smoothly for 17 years without any problems. Another rainwater facility designed by Professor Han, at Star City in Gwangjin-gu, has also been working perfectly for 20 years now. At first, Professor Han just wanted to use rainwater for flushing toilets, but over time, his technology improved so much that now it’s being used for drinking water in places like Cambodia. The ways to use rainwater have really expanded.

Professor Han’s message—“Let’s manage all water, by everyone, for everyone”—was even chosen as an official agenda item for the 2026 UN Water Conference.

Through BiTS and Rain School, students have become more cheerful and the whole village environment has improved. The shared rainwater drinking facilities have been a real success at the community level and are now about to spread even further. Instead of having to buy expensive bottled water, people can drink whenever they want as long as they have a bottle. For now, it might just be about drinking water, but if these students graduate, go out into society, and the activities that transformed their village continue on for another ten years, it could end up changing all of society—and maybe even a country.