Art history remains integral in understanding bygone times. In particular, it works to help answer two crucial questions: What was considered the “ideal” life of an era for the people who lived in it? Considering this, what did the everyday life of an era and people actually look like? These are the curiosities the Seoul National University Museum aimed to address in their latest exhibition titled The Ideals and Scenes of Life in Korean Art. From April 1 to June 28, this exhibition is open to the public in the Traditional Art Hall of the SNU Museum.

Poster for the Exhibition

The exhibition is divided into two sections. The first, titled The Ideals of Life in Korean Art, explores how ideals such as achieving professional success, leading a moral and virtuous life, and leaving lasting legacies are instilled in traditional paintings and writings. The second, titled Scenes of Life in Korean Art, offers a glimpse into past lives through showcasing traditional crafts and letters exchanged between individuals.

Ideal Life of a Military Official

Pushing past the black curtains at the entrance to the exhibition hall, visitors are granted access to an isolated slice of life in Korean history. A Pyeongsaengdo is a style of folding screen painting unique to the late Joseon Dynasty that depicts a nobleman’s ideal life, such as the desire to curate a peaceful home and the aspiration to achieve a successful career. Each panel illustrates moments of life in chronological order, including scenes such as a first birthday party, wedding, and 60th anniversary of a marriage. Though most Pyeongsaengdo screens typically follow the life of a literary scholar, the piece titled Ideal Life of a Military Official instead chooses to follow the life of a military figure. Eight scenes are presented in this creation, including a Doljabi, an event during a child’s first birthday to predict their future, scenes of war, and the procession of the Minister of War.

Rubbing of the Epitaph on the Monument for King Gwanggaeto

Seeking ways to preserve important records long into the future, politically, culturally, and historically significant writings were often inscribed on stone slabs and erected as steles. Such inscriptions were sometimes used as stamps to transfer the text onto paper for distribution to a wider audience. Through these stone steles, we are able to stand witness to our ancestors’ wishes to pass down history.

In four monumental pieces, a copy of the Rubbing of the Epitaph on the Monument for King Gwanggaeto extends from ceiling to floor, spanning the entire length of the room. Each piece is a print of a different side of the monument. Erected in 414 by King Jangsu to commemorate his father, King Gwanggaeto, the stele is currently located in Ji’an, China. Standing at 6.39 meters tall, it is inscribed with 1,775 characters that detail the founding myth of Goguryeo, the king’s ascension to the throne, King Gwanggaeto’s accomplishments, and the Sumyoje (a system for managing royal tombs). The monument was rediscovered in 1877 after a long period of neglect following the fall of Goguryeo, and has since become a rare source for studying Northeast Asia in the 4th and 5th centuries.

A Messenger Box Used to Carry Letters

A more intimate glimpse into life during the Joseon Dynasty is provided in the form of letters by the names of seogan and ganchal. These were the primary modes of communication and now serve to document the unfiltered emotions people of the past poured into their writing. From a father chiding his son to an official expressing concern for public welfare, these letters highlight the everyday aspects of life that suggest the past is not so different from our present. Included in this collection is the Letters by Park Jiwon, in which a Silhak scholar writes to his sons in an unembellished manner about private matters.

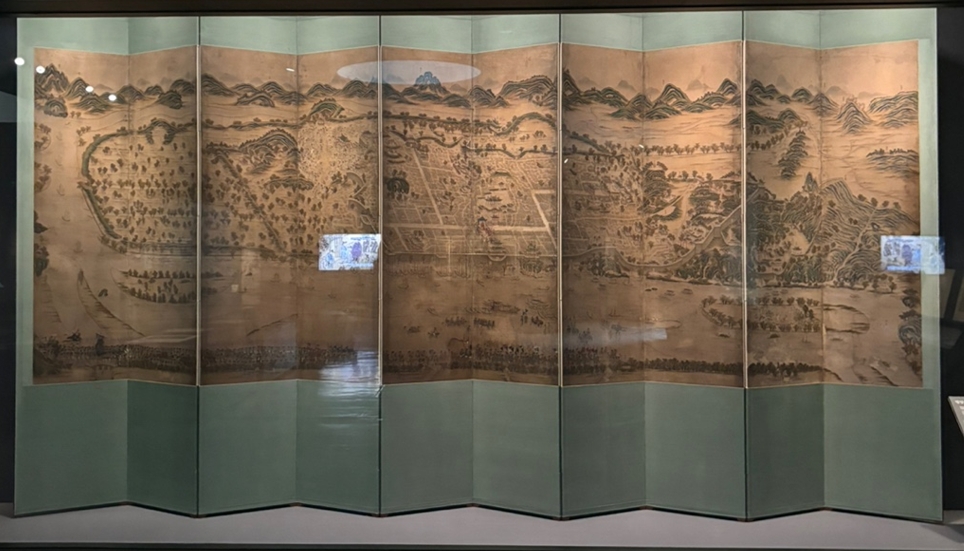

Scenery of Pyeongyang

One of the highlights of this exhibition is the Scenery of Pyeongyang, which was recently restored. As the second most populous city in late Joseon, Pyeongyang was famed for its picturesque landscape and flourishing culture, thus becoming an artistic hotspot. This folding screen painting serves as both a historical record — capturing daily life and landmarks—and a window into the urban culture of late Joseon. Painted from a bird’s eye view, the screen depicts ordinary moments such as a pansori performance, folk games, people fishing and doing laundry by the river.

Celadon and Porcelain Crafts

Near the end of the exhibition, visitors pass by a collection of crafts ranging from bronze mirrors to porcelain kitchenware. These, aside from serving their intended practical purposes, also acted as aesthetic decorations, brightening up people’s everyday lives. The aesthetic qualities of these craftware can be seen through intricate engravings, the soft green glaze of celadon, and the refined elegance of white porcelain. Together, these serve to demonstrate the intrinsic nature of beauty and art in Korean culture.

The exhibition as a whole serves to connect us with the past. Ideals persist despite the passage of time, and life tends to repeat itself through generations. This exhibition is open for the first half of this year, and visitors to the museum are encouraged to stop by and appreciate this historic look into life.

Written by Eusun Lee, SNU English Editor, sunnylee006@snu.ac.kr