The SNU Institute for Contemporary Korean Studies (SNUCKS) has launched an insightful and dynamic new series of monthly colloquia led by the K-Narrative team, titled “Narrating Contemporary Korea.” Held once a month on campus, the series examines the cultural implications of Korean narratives across literature, film, television, and digital media. It offers a timely forum for understanding how these stories reflect and reshape modern Korean desires, identities, and anxieties.

Led by Professor Shin Hyoung Cheol from the Department of English Language and Literature, the K-Narrative team mainly explores two central questions in their project: Do contemporary Korean cultural products share a meaningful narrative commonality—a masterplot that ties them together? If so, can this narrative be understood as distinctively Korean in a way that justifies the ever-expanding use of the “K” prefix? Insights from the K-Narrative team will culminate in a forthcoming volume, tentatively titled Narrating Contemporary Korea, to be published in the Palgrave Korean Studies Series by Palgrave Macmillan.

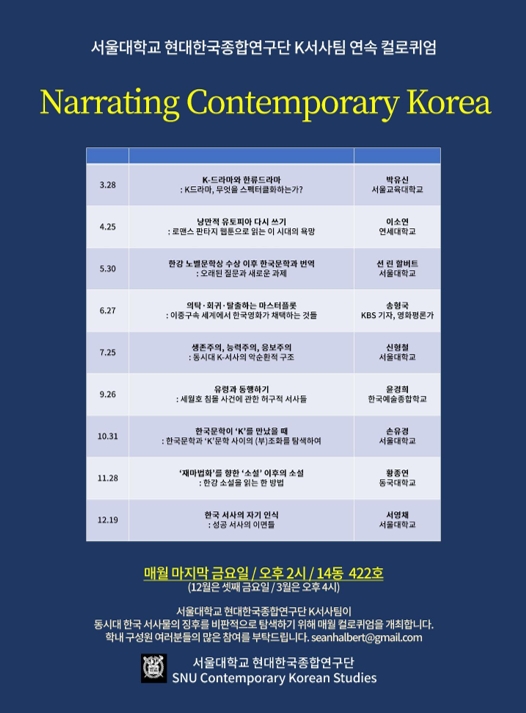

Poster advertising the “Narrating Contemporary Korea” Colloquia led by the K-Narrative Team

The inaugural session of the series took place on March 28 and featured Professor Park Yu Shin of Seoul National University of Education (SNUE), a scholar of media literacy and art education. Her lecture, titled “K-Drama and Hallyu Drama: What Does K-Drama Turn into Spectacle?” delved into the global rebranding of Korean television and traced how the term for Korean dramas has evolved in media discourse.

Her talk set the tone for the colloquium by blending cultural critique with personal insight. Professor Park introduced her lecture as an accessible, fan-centered reflection rather than a theoretical or academic presentation. As someone who grew up before the term K-Drama even existed, she traced how Korean television evolved from a regional cultural product into a globally recognized export. Her central inquiry—why global media and industry actors have come to prefer the term “K-Drama” over “Hallyu drama”—was part of a broader exploration into Korean dramas as a key facet of the wider “K-phenomenon.”

Professor Park delivering her talk

According to Professor Park, the term Hallyu (Korean Wave) emerged in the late 1990s following the Asian Financial Crisis, which made Japanese TV licenses prohibitively expensive in regional markets. This shift opened the door for Korean dramas, relatively low-cost but high in quality, to take center stage. These dramas gained unexpected popularity across Asia and beyond, even when not originally intended for international audiences. Landmark titles such as Dae Jang Geum (Jewel in the Palace) resonated widely, including in countries like Iran, where it achieved record-breaking viewership. Gyeoul Yeonga (Winter Sonata) notably achieved immense popularity in Japan, which helped to reshape perceptions of Zainichi (Japanese Koreans). In the United States, Korean dramas first circulated through pirated DVDs, fan subtitles, and grassroots online communities, many led by non-Koreans, long before streaming platforms like Netflix came into play.

Professor Park then posed a fundamental question: Who is watching Korean dramas, and why? Drawing on survey data and critical reviews, she outlined several recurring themes laid out by media critics. Many suggested that viewers are drawn to the emotional sincerity, family bonds, moral clarity, and romantic storytelling typical of K-Dramas. She also noted the frequent use of stylistic “emotional interludes”—brief moments in which a character’s inner emotions are revealed through flashbacks, imagined scenarios, or dramatic slow-motion montages. Such techniques have come to be recognized as hallmarks of Korean storytelling.

Per Professor Park, the shift in discourse from Hallyu drama to “K-Drama” occurred with the proliferation of Korean content on global streaming platforms like YouTube and Netflix. The term “K-Drama” was particularly actively used and promoted by state-sponsored organizations such as the Korea Tourism Organization. She noted how the Korean government specifically appears to have begun labeling its cultural products with the “K” label to enhance exportability—a nationalist strategy aimed at positioning Korean culture as a marketable commodity. Meanwhile, in Western news media, titles like The Glory had begun to be widely described as “K-Dramas” by 2023. What was once a niche fandom had effectively now become a mainstream cultural asset. To this, many critics point to Korean dramas’ consistent portrayal of social hierarchies, systemic injustice, and underdog protagonists as key reasons for their resonance in an increasingly globalized world.

Referencing a range of recent articles on K-Dramas, Professor Park calls attention to a view among Korean critics that global success hinges less on quality than on genre. These pieces suggest that K-Drama now denotes genre-driven fiction primarily tailored to U.S.-centric audiences. In other words: genre spectacles. To this, Professor Park expressed concern over why American viewership is still seen as the default benchmark for global success. Turning to FlixPatrol, a data-tracking platform for global streaming, she found that actual viewership trends tell a different story. There, she found that in 2024, the most-streamed Korean drama was not a high-budget thriller, but a romantic melodrama, Marry My Husband. Other romance titles like My Demon ranked highly in Argentina and Bahrain, while King the Land found enthusiastic audiences in Bangladesh, Chile, and Colombia. Such findings challenge the assumption that only gritty, action-heavy dramas resonate internationally. Yet, within Korea, these globally popular titles are often overlooked, as media narratives continue to focus on U.S. market performance as the standard of success.

Contrary to popular belief, the so-called “typical” Korean dramas, often dismissed as sentimental or formulaic, are in fact some of the strongest performers worldwide. Professor Park observed that high-budget productions with extensive international marketing often underperform, while more modest “domestic” dramas, never intended for global release, attract large international audiences. Ironically, the very dramas viewed as outdated or overly emotional by Korea’s cultural elite are resonating most powerfully with global viewers. Yet these successes often remain invisible in official reports or media coverage. Such misreading of the data will become dangerous for the future fate of Korean dramas: If the industry continues to misunderstand what truly drives global popularity, it will continue to invest in projects that fail to deliver.

Professor Park concluded by returning to a simple but powerful question: Why do people love Korean dramas? To this, she offered a deceptively straightforward answer. It may be because Korea is a “drama republic.” That is, the drama form is deeply embedded in Korea’s media landscape and cultural fabric. As such, rather than forcing domestic dramas to fit a global mold, the industry should instead recognize that what has long worked for Korean audiences also works internationally. The emotional intensity, melodrama, family dynamics, and moral clarity characteristic of traditional Korean television may be its greatest cultural asset. She also emphasized that recurring narrative tropes, such as chaebol families, adoption arcs, and the ever-popular secret child plot, are more than just clichés. They reflect deep-seated cultural and historical concerns. The prevalence of birth-switching narratives, for instance, connects to Korea’s historical traumas of war, poverty, and displacement, and serves as a collective mechanism for processing social rupture. These dramas, rooted in lived experience and cultural memory, offer viewers a site of emotional negotiation and connection.

In closing, Professor Park asserted that Korea’s most successful cultural exports have not been engineered—they have been organic and sincere. As the industry looks ahead, it would do well to remember that.

Attendees at the talk

For those interested in more insightful talks like Professor Park’s, the K-Narrative Colloquium continues throughout the year with sessions exploring contemporary Korean storytelling across media. Upcoming topics include desire and romantic fantasy in webtoons (April 25), Korean literature and translation in the wake of Han Kang’s Nobel Prize (May 30), cinematic masterplots in Korean film (June 27), cycles of survivalism, meritocracy and retributivism in K-narratives (July 25), fictionalized accounts of the Sewol Ferry disaster (September 26), the tensions between Korean literature and “K”-branding (October 31), and post-novel fiction and re-enchantment through Han Kang (November 28), and the series will conclude on December 19 with a reflection on the hidden layers beneath success-driven narratives in Korean fiction. We warmly invite the SNU community to join the conversation.

Written by Hyun Kyung Jung, SNU English Editor, jhyunk@snu.ac.kr