On December 6, Pulitzer Prize-winning author Junot Díaz delivered an engaging lecture titled “Critical Worldbuilding or How to Understand America in 20 Minutes” at the SNU College of Humanities. Co-hosted by the Institute of American Studies, the Institute of Latin American Studies, the Department of English Language and Literature, and the American Studies Association of Korea, the event drew a diverse audience eager to gain insights from one of contemporary literature’s most influential voices. Junot Díaz is known for his world-renowned novel The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao (2007) and other bestselling publications, and is currently a professor of Comparative Media Studies/Writing at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

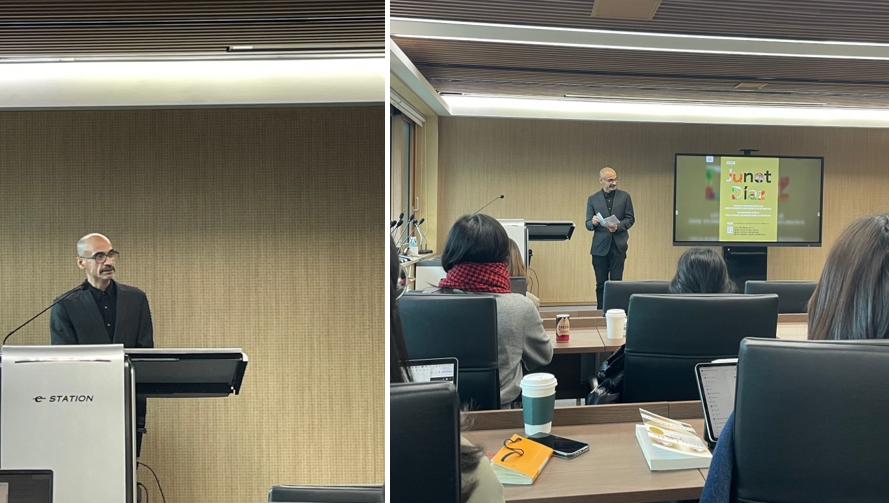

Professor Junot Díaz delivering his talk

In the lecture, Professor Díaz discussed concepts of storytelling, worldbuilding and their engagement with dominant narratives such as the myth of the American frontier. He explored how worldbuilding has increasingly become a central aspect of mass global culture, with much of popular entertainment today conceiving vast multiverses of imagined worlds. According to Professor Díaz, the creation of a world requires the construction of coherent, immersive settings complete with their own rules, physics, and social matrices. Quoting Professor Henry Jenkins, a renowned media scholar, he traced the evolution of storytelling in American cinema, from the early focus on singular plots to character-driven narratives, and finally to an emphasis on worlds as the core element of popular stories. Today, franchises like the Marvel Cinematic Universe and Star Wars epitomize this emphasis, where audiences are expected to carry knowledge of these worlds across various texts and media.

The poster for the event

Although world-building often seeks to imagine radical realities that can inspire political and social progress, Professor Díaz contended that, in practice, it is hegemonic and reifies the very same existing societal norms and power structures it claims to promise escape from. One recurring trope is the “frontier myth,” a foundational narrative of American identity. This myth depicts the United States as a moral landscape defined by borders—civilization versus wilderness, white settlers versus Native Americans. At the heart of the myth is the figure of the rugged individualist, the American frontiersman, who must cross into the wild Native American territory. Here, he must experience regression to a more primitive and natural condition to discard the false values of corrupt civilization and enact a new social contract. This figure encounters conflict with the wilderness, represented as a violent, racialized other, and through this conflict, experiences a transformative redemption that purportedly rejuvenates the American spirit. The frontier is thus framed as a site of regeneration through violence, where the frontiersman emerges as an independent, true American hero who overcomes both the corruption of civilization and the perceived savagery of the wilderness.

This myth is deeply embedded in the cultural psyche of the United States, serving as a foundational romance through which Americans understand their identity and exceptionalism. It continues to resonate in modern cultural narratives. For instance, in Avatar, the protagonist, Sully, abandons the corrupt Earth and regresses to the “primitive” Na’vi world, only to emerge as their savior. In zombie narratives, the apocalypse transforms the world into a new frontier, where survivors regress to a primal state and engage in a “race war” against the zombies, often depicted as an irredeemable, racialized other. Similarly, superhero narratives often glorify the protagonist’s rejection of societal norms and their use of extraordinary power to impose order. Characters like Batman embody this frontier mentality, emphasizing individual supremacy over collective efforts to fight the criminal others.

Despite claiming to critique civilization, such narratives often reinforce the hegemonic notion that progress arises through violent conquest and domination. Professor Díaz highlights the troubling implications of these frameworks, where the racialized other frequently becomes a tool for the protagonist’s self-discovery and empowerment. He argues that such narratives discourage alternative ways of imagining community, solidarity, and resistance, instead perpetuating reductive and harmful societal hierarchies. It thus becomes crucial to actively deconstruct these conventional frameworks and reimagine them in subversive ways to explore themes of reconciliation and coexistence.

Professor Díaz’s talk was a compelling reminder of the humanities’ ability to interrogate cultural assumptions and inspire meaningful dialogue, leaving the audience with a deeper understanding of the narratives that define our world and the tools to reimagine them. For those interested in talks like these, stay updated to the events posted by the various institutes of SNU.

Written by Hyun Kyung Jung, SNU English Editor, jhyunk@snu.ac.kr